I still remember the day one of my students looked me in the eye and said, “Dr. Mainaly, why should I research when Grok already knows?” The whole class laughed, but I laughed louder—partly because I didn’t want to cry. That, my friends, was the moment I realized we had officially crossed the threshold into what I call the Age of Grokipedia—a place where curiosity goes to nap, where recursion languishes, and where students think “freewriting” is what happens when ChatGPT doesn’t ask for a subscription. Once upon a pre-AI time, Wikipedia was our global campfire of knowledge. You could fall down rabbit holes for hours. One minute you were reading about the French Revolution; three clicks later, you were learning about the migratory patterns of penguins and the mysterious death of Rasputin. There was joy in that meandering. It was inefficient, chaotic, recursive, and profoundly human.

Wikipedia taught an entire generation to think associatively. The hyperlink was our cognitive trampoline. We bounced between ideas, connecting dots that no algorithm would have thought relevant. Students would arrive in class with wild connections—like linking Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar to Game of Thrones politics—and I’d grin because that was learning: messy, recursive, unpredictable, alive. But then came Grokipedia—that glossy AI-infused hybrid of Grok, ChatGPT, and every other model pretending to be your friendly, know-it-all neighbor. And suddenly, the journey of knowledge became an elevator ride: push a button, reach the answer, no scenic route, no sweat.

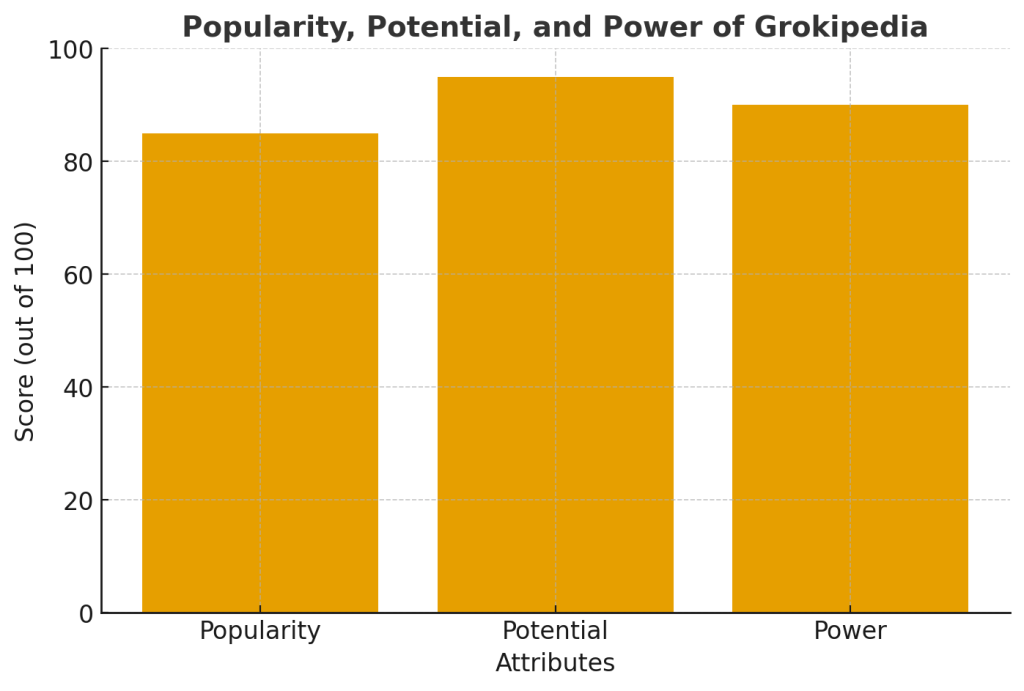

Grokipedia (let’s just admit we’re calling all AI-aggregated answer engines this now) is like Wikipedia’s overachieving cousin who shows up to family gatherings wearing AR glasses and says, “I don’t read anymore—I synthesize.” In theory, Grokipedia democratizes information faster than Wikipedia ever could. Ask it anything—“Why did Caesar cross the Rubicon?”—and it’ll not only tell you why but also give you a three-sentence summary, five related memes, and a citation list formatted in APA 7th edition. It’s dazzling. It’s addictive. It’s also quietly corrosive. As an English professor teaching research and writing, I’ve noticed that Grokipedia’s instant-answer culture is killing what I call the cognitive composting process—that slow, recursive, slightly smelly phase of thinking where half-baked ideas decompose into genuine insight. My students no longer want to marinate in confusion; they want precooked clarity. They want AI microwave meals for the mind. And I can’t entirely blame them. Who wouldn’t? Grokipedia is fast, fluent, and frighteningly confident—like a student who’s never read the book but still dominates the discussion board.

Recursivity is the lifeblood of writing. It’s the act of looping, revisiting, rewriting—of discovering what you think only after you’ve written what you don’t. It’s Anne Lamott’s “shitty first draft,” it’s Peter Elbow’s “writing to learn,” it’s every 3 a.m. coffee-fueled revelation that comes after you’ve typed, deleted, and retyped the same sentence fifteen times. But AI doesn’t loop—it leaps. It jumps straight to the polished version, skipping the chaos that makes writing worthwhile. A few weeks ago, one of my graduate students proudly told me she had finished her “recursive writing assignment” in two hours using ChatGPT. I asked her how she revised. She blinked and said, “Oh, I just hit regenerate.” That was the moment I realized recursion had become a button, not a process.

Teaching research writing in 2025 feels like teaching swimming in a world of teleportation. Students don’t want to wade into sources; they want Grokipedia to beam the synthesis directly into their brains.When I assign an annotated bibliography, I now have to specify: No, you may not ask Grok to annotate for you. One student once submitted this line in her reflection: “I asked ChatGPT to reflect on what I learned, and it said I learned about myself.” I had to admire the poetry of that. Meta, posthuman, beautifully ironic. But it also revealed something tragic: the erosion of epistemic struggle. Students are outsourcing not just answers but the process of asking.

In the past, prewriting was a social ritual. We brainstormed, mapped, doodled, argued, doubted. Now, students “prompt.” The presearch phase—where they once stumbled upon unexpected treasures—has become a prompt-crafting exercise. I miss the days when students would misinterpret a source spectacularly and then spend days wrestling with their misunderstanding until insight dawned. That’s where growth happened—in the recursive wrestling match, not in the AI-generated peace treaty.

I try to cope with humor. One day, I told my class, “Imagine if Shakespeare had Grokipedia.” He’d type: ‘Summarize Julius Caesar in iambic pentameter.’ And Grokipedia would respond: ‘Friends, Romans, countrymen—.’ Or imagine Socrates with Grok. “Hey, Grok,” he’d say, “What is virtue?” And Grok would answer, “Virtue is adherence to moral excellence, as defined by…” And Socrates would frown, shut down his tablet, and say, “Well, there goes philosophy.” Humor aside, the flattening of thought worries me. I see students losing patience with ambiguity. They no longer tolerate not knowing. That, to me, is the new dementia—not clinical, but cognitive: a kind of recursivity dementia, where the brain forgets how to wander, how to circle back, how to doubt and deliberate.

In my own research life, presearch is where the magic happens. Before I write an article, I spend weeks just exploring—walking around with fragments of thought, scribbling metaphors on napkins, having arguments with myself. I once wrote half a paper in my head while standing in line at a goat farm near Memphis. That aimless intellectual grazing—pun intended—is essential. It’s how ideas ferment. But Grokipedia makes fermentation seem inefficient. It hands you distilled whiskey before you’ve even planted the barley. I’ve caught myself falling into this trap too. While writing my article “AI, Woke Pedagogy, and the Politics of Inclusion,” I asked ChatGPT (yes, you!) for “key arguments about algorithmic bias in writing pedagogy.” You gave me a gorgeous outline in 20 seconds. But something felt wrong. It was too neat. Too coherent. Too… unearned. So I spent the next two weeks unraveling what you gave me—arguing with it, re-reading my notes, and finally realizing that the argument I truly cared about was buried in what you didn’t say. That’s recursion: finding your voice in the echo of the machine.

When I say “dementia,” I don’t mean the medical condition. I mean a kind of cognitive forgetfulness—a systemic decay of memory and context. Grokipedia gives us answers without ancestry. It’s the opposite of archival thinking. It doesn’t remember how it knows; it just knows. My students used to trace knowledge genealogies—who said what, when, and why. Now, they just ask, “Who said it first on the internet?” Grokipedia, in its efficiency, erases the messy human lineage of knowledge. It forgets the journey of ideas. And when knowledge forgets its ancestry, we all suffer collective amnesia. We become like that friend who tells a great story but can’t remember where they heard it—only that it “came from TikTok.” Wikipedia, for all its faults, preserved the genealogy. Every article had “Talk” pages, revision histories, arguments. It exposed the construction of knowledge. Grokipedia hides it behind velvet AI curtains, whispering, “Don’t worry about the how—just trust me.”

Wikipedia was built on communal effort. It thrived on collective curiosity and open debate. Anyone could edit (and argue endlessly in the comments). Grokipedia, by contrast, feels like a gated mansion. It borrows knowledge from the commons, processes it through proprietary models, and returns it polished—but detached from its communal roots. When I tell my students this, they shrug and say, “But Grok gives better answers.” Sure it does. But at what cost? Wikipedia taught us to be skeptical. Grokipedia teaches us to be satisfied. Wikipedia was messy democracy. Grokipedia is benevolent dictatorship. Wikipedia said, “Here’s a start—go explore.”

Grokipedia says, “Here’s the conclusion—don’t bother.” And yet, Grokipedia isn’t the villain. It’s just a mirror reflecting our impatience. We’ve become allergic to slow cognition. We’ve mistaken access for understanding.

To fight this cognitive atrophy, I’ve started assigning “Analog Days” in my graduate seminars. Students must bring pen, paper, and no devices. We spend an hour freewriting—no prompts, no AI, no Googling. Just thinking with the hand. At first, they fidget like caffeine-deprived squirrels. But after ten minutes, something beautiful happens. Silence fills the room, pens begin to dance, and by the end, they’re smiling like archaeologists who’ve unearthed something ancient—their own thoughts. One student told me afterward, “I felt my brain breathing again.” That’s the moment I live for. That’s the antidote to Grokipedia dementia.

Don’t get me wrong—I love AI. I use it to brainstorm, summarize, and occasionally finish a sentence when my caffeine fails me. But I treat it like a co-author who’s too efficient for its own good. I let it suggest, not decide. There was a time I asked Grok to “explain ambient rhetoric in a funny way.” It responded, “It’s like when your Wi-Fi drops, and suddenly you understand Heidegger.” I laughed for ten minutes straight. But then I spent hours thinking about it—and wrote an entire conference paper. That’s the kind of recursion we need: the dance between absurdity and insight. If I were to diagnose our collective state, I’d call it Languishing Recursivity Syndrome (LRS)—a chronic condition marked by impatience with ambiguity, overreliance on AI synthesis, and an inability to dwell in discomfort.

Symptoms include:

- Finishing essays before starting them

- Confusing coherence with thought

- Mistaking regurgitation for reflection

- Saying “that’s enough research” after a single AI query

Treatment? Reintroduce friction. Write badly. Revise repeatedly. Wander Wikipedia without purpose. Ask Grokipedia why it thinks what it thinks. Make thinking hard again. Despite my teasing, I’m not anti-AI. I’m pro-recursion. I believe Grokipedia can be reimagined not as a replacement for Wikipedia, but as its recursive partner—a system that shows its sources, reveals its revisions, and encourages readers to argue back. Imagine if Grokipedia had a “Doubt Mode.” Every time it answered, it also whispered, “But what if I’m wrong?” Imagine if it showed the journey of its thought—the sources it weighed, the ones it ignored, the uncertainties it suppressed. That’s the kind of AI I’d trust in my classroom: one that models intellectual humility, not omniscience.

Last semester, a student turned in an essay titled “The Recursive Nature of Grok.” It was beautifully written—too beautifully. I asked if she’d used AI. She said, “Yes, but I told Grok to ‘write like me.’” “Did it work?” I asked. She paused. “Better than me,” she admitted. We both laughed, but the irony wasn’t lost on either of us. The machine had learned her voice, but she hadn’t yet learned her own. That’s the danger: when we let Grokipedia speak so fluently for us that we forget what our own intellectual accent sounds like.

So here I am, looping back to where I began: my student’s question—“Why should I research when Grok already knows?” Because, dear student, Grok knows, but it doesn’t remember. It answers, but it doesn’t wonder. It summarizes, but it doesn’t struggle. And struggle is sacred. Without recursion, knowledge is static. Without presearch, discovery is sterile. Without freewriting, voice is ventriloquism. So I’ll keep teaching the loop—the messy, recursive, self-contradictory loop of learning. I’ll keep sending students into the labyrinth of Wikipedia and beyond. I’ll keep reminding them that curiosity is not a query; it’s a pilgrimage. And maybe someday, when Grokipedia learns to forget just enough to wonder again, we’ll all rediscover the joy of thinking in circles.